When I was a kid, my family wouldn’t think to embark on a road trip without a TripTik in the glove box. These small, spiral-bound notebooks (a relic of pre-digital times) were convenient travel guides, personalized by AAA for its members on a trip-by-trip basis. Before GPS or Google Maps, TripTiks included paper map sets annotated with highlighted routes, detailed traffic notes and suggested attractions along the way. They were roadmaps, designed just for you, giving travelers confidence and comfort that the experience and judgment of experts could help them navigate unfamiliar terrain.

View this post on Instagram

Designing an airport terminal is, of course, considerably more complex than planning a vacation. But in some fundamental ways, leading a complex architectural project is not too unlike putting together a TripTik. As architects, it is our responsibility to leverage our expertise in guiding a client along the most efficient path shaped by that project’s circumstances. It’s the roadmap for the project that brings it all into focus: communicating an understanding of milestones with expectations for an end product. Moreover, since every project is different, we must customize a process that works for that project, that location, that context, and curate a team of specialists that can deliver on our client’s expectations.

We help to clarify all of the stakeholders important to a project, and work to understand their individual goals. Though new technologies have perhaps overtaken the more personalized touch of the TripTik, architects can’t afford to sacrifice that one-on-one engagement — even as the tools of our trade also continue to change. At the end of the day, project management is about leading people, and inventing a process for teamwork tailored to the needs and imagination of our clients. Communication is key.

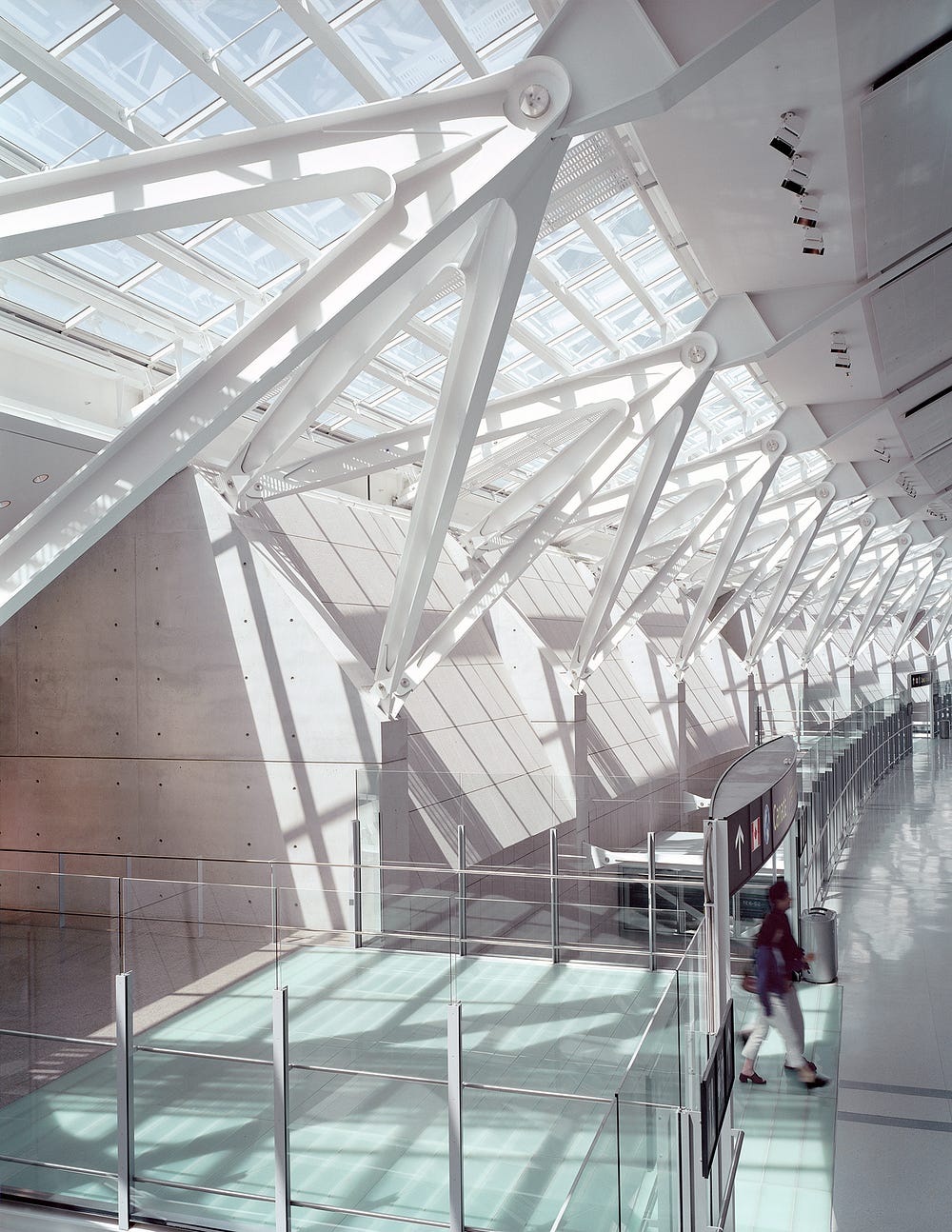

This is especially true for the development of a new airport terminal. I’ve had the privilege of working on a number of aviation projects that have shaped SOM’s transportation portfolio over the years, but Toronto Pearson International Airport’s Terminal 1 always sticks out in my mind. Terminal 1 was the result of a collaboration with Adamson Associates and Moshe Safdie, and a project we had to build out quickly in response to the urgent need to accommodate a projected 60 percent passenger increase over the next 20 years. As Toronto’s profile rose (and continues to rise) on the world stage, our interdisciplinary team was determined to design a terminal to match the city’s ambitions. The project presented challenges requiring unorthodox solutions, and gave our team the opportunity to think above and beyond more traditional concerns for longterm airport management and user experience.

Building from the top down

Airport architecture inherently brings with it a complex set of concerns intersecting design, structural engineering, and planning. Add to that mix an expedited schedule and the need to work around an active terminal, and the stakes increase quite a bit. Yet as demanding as an accelerated construction schedule could be, this challenge was par for the course in terms of leading the team through the multiple moving parts of building an airport. More than any technical matter, the most unpredictable element of an airport project is, well, people. Being able to adapt to the changing needs of a client is paramount for any architect, but the number of stakeholders involved in a big transportation project (city governments, regulatory agencies, private partners, service providers) greatly increases the complexity of managing such expectations.

More than any technical matter, the most unpredictable element of an airport project is, well, people.

By the time construction began on Terminal 1, some big changes at Pearson International Airport were still unfolding. An ongoing merger of two major airlines meant even the most basic aspects of the layout of the terminal were in flux. We were also waiting on a pending memorandum that would determine the degree of commingling of passengers and the forecast of traffic allocations between domestic, international, and American-bound flights. These shifting mandates began a process that I believe highlights our expertise. We instinctively pulled from our past experiences to prepare a variety of solutions that would be ready once final determinations were made.

Taking the fast track amidst fluid circumstances meant making decisions that would give us maximum wiggle room. We knew early on that the roof would determine the form of the terminal itself, so we decided to build from the top down. This gave our team the ability to continue interior design development while moving forward with construction. To get the most out of a hastened schedule, we started with a new access road which could be used first as a platform for building out the swooping roof structure.

Designing from the bottom up

Beyond these more immediate issues, our team also had to anticipate the future needs of an often-forgotten user: airport staff. Ongoing maintenance, for instance, is an important and sometimes overlooked design parameter. But the cost of ignoring this factor during the early stages of airport development can grow exponentially over time as individual fixtures become outdated, or the structure as a whole begins to age. With the long view in mind, our team laid out detailed plans at both small and large scales to accommodate maintenance and make it more efficient. A special mock-up room was built so that samples of every fixture could be studied and tested, ex situ, to determine just how difficult it might be to repair or clean. Even the ceiling panels were customized to meet the needs of those who might need to replace them years down the road. We literally asked, “How many people does it take to screw in this lightbulb?” From the scale of the largest structural elements to the most minute details, keeping our team on the same page with contractors, stakeholders, the client, and ultimately the client’s employees, was essential to delivering the best possible terminal.

This level of coordination was even more crucial to enable the smooth functioning of Terminal 1’s “swing gates,” which can convert between international and U.S.-bound, or U.S.-bound and domestic operations as needed. The changeover from one mode of operation to the other is a complex choreography involving security checks, the moving of sliding glass walls, and the use of dynamic signage to accommodate very different boarding and deplaning procedures. Because these swing gates change the physical layout of the terminal, we devised a tool that could help airport staff navigate the shifting topography. This tool eventually took the form of a map printed on a wearable card — an easy-to-use reference guide for staff during operational changeover. In building an airport capable of running at peak efficiency, communication itself becomes an important design feature.

Of course, we also took the greatest care in applying this insight to the passenger experience. How easily any person is able to navigate through the space of an airport terminal is a matter of great consequence — flights made or missed, bon voyage or travel nightmare. It is critical to understand that each user may have different needs. Beyond complying with codes and best practices for accessible design, we wanted to provide an intuitive experience of moving through the terminal for everyone. To this end, our team brought in volunteers from the Canadian National Institute for the Blind to help test the effectiveness of our wayfinding systems — from the size and color contrast of lettering, to scale and legibility of pictograms and directional arrows. Listening to their feedback about what worked or didn’t gave us invaluable insight into how our design might address a plurality of needs.

The armature that enabled us to achieve so much in such little time was not forged in steel or concrete. The foundation of great architecture is communication. Effective project leadership helps translate the big vision of a design into the everyday experience of that vision. How do we make this work? How can we adapt in the short and long terms? How can we best serve stakeholders and the public? An open conversation with clients, stakeholders and consultants is just the starting point; successful dialogue also requires platforms for receiving and managing comments, clear record-keeping, and distribution of project knowledge. It can all sound daunting, but this is where we excel. We make road maps tailored for the journey that clients and stakeholders want and need — a map that will make the trip less bumpy and, hopefully, richer and more engaged.

Laura Ettelman is a Managing Partner based in SOM’s New York office. Well-versed in leading large, multidisciplinary teams, she contributes her expertise to airports and other transportation projects around the world.